on

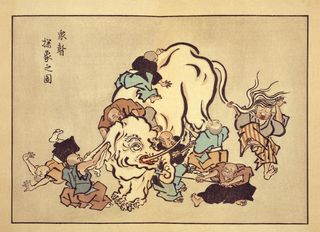

Framing Ambiguity, Incentives, and Actions

In the mid 90s, while working in government, I was given an invaluable bit of advice from an Air Force colonel who would become a trusted advisor and a dear friend. He said:

“Perspective is elusive… I’ve worked with countless Ph.D.’s that would obsess over details which did not matter in the grand scheme of things. You seem to have the ability to operate on multiple levels. Don’t lose the ability to see the bigger picture."

At the time, I understood the specific context that compelled him to share this advice; yet I didn’t appreciate the broader significance of this statement.

Years later, as a researcher in the national security community, I routinely questioned myself about how I was approaching a particular challenge. Was my view of the problem too narrow in scope? Was I missing larger opportunities for impact by focusing on a smaller, more tractable problem?

My mission as an applied researcher was to seek transformational advancements in the capabilities of our sponsors. It demanded that I scan for opportunities at the edges of what was currently understood and at the intersections of domains where creative combinations of ideas offered better odds for significant advances.

Operating in the gray areas was tough. While our organizational mission was clear, the day-to-day demands for signs of progress pushed many towards incrementalism. Problems were defined with the veneer of risk-taking and innovation but the reality often fell short. While failure was valued in theory, in practice it was an uncomfortable outcome tolerated by few.

It was during these years that I began to appreciate the cognitive burden associated with pursuing the uncertain path. It necessitates that we struggle with a number of internal forces. At the core of this struggle, I believe, is a confrontation with loss aversion - our bias toward mitigating loss at the expense of potential gains.

In the context of organizational decision-making, loss aversion leads to often frustrating and predictable outcomes. Higher risk initiatives with the potential for significant benefits are evaluated in the context of organizational risks that are invariably clearer, such as reputational and monetary losses incurred with failure. When faced with known downside risks, uncertain upside potential, and limited perceived options for recovery, many opt to avoid challenging the established order. This has profound implications in how solutions are framed for complex problems.

In the face of rampant complexity, problem definition and solution development are naturally intertwined and iterative. One learns about the problem by taking actions to test hypotheses. I watch with curiosity to see how others frame their approaches to complex problems. How much of the complexity do they choose to embrace? What frame of reference do they take? How is that shaped by the context they are embedded in?

Routinely I see others adopt and retain a narrow frame in the interest of expediency. It is perfectly reasonable and warranted to decompose a problem into subproblems that are more tractable. The difficulty comes when one stops trying to situate local actions in the broader context; in those cases, the opportunity is missed to question whether local actions are supporting positive outcomes on a larger scale.

As we wrestle with the toughest challenges of our time, this behavior will continually hinder our progress. At the extremes, even with thoughtful reflection, it is impossible for a single individual to conceptualize and hold a representation of the problem in mind. The complexity is simply too vast. Problem definition and solution development naturally become group activities out of necessity. This requires enlightened organizational leadership that sees the larger opportunities and builds the collaborative coalitions that enable scalable impact. At the level of the individual, it requires humility about the extent of our knowledge and willingness to continually question our present framing of the challenges before us.

The resistance to embracing this mindset can be strong. When a long-held frame of reference is questioned, feelings of unease and insecurity may drive a strong negative reaction. The longer a fixed view has remained the intellectual foundation for decision-making, the more difficult it becomes to revise that view. Compassionate leadership will be necessary to help others expand their perspectives and guide those who are willing toward larger opportunities.

The years ahead are rife with possibilities. We are learning more and more each day about the human condition. It is with this perspective that we have the opportunity to create new organizational models to meet the challenges of our time. I’m looking forward to participating in this process of experimentation and redefinition.